Automated Culvert Design

(2018)

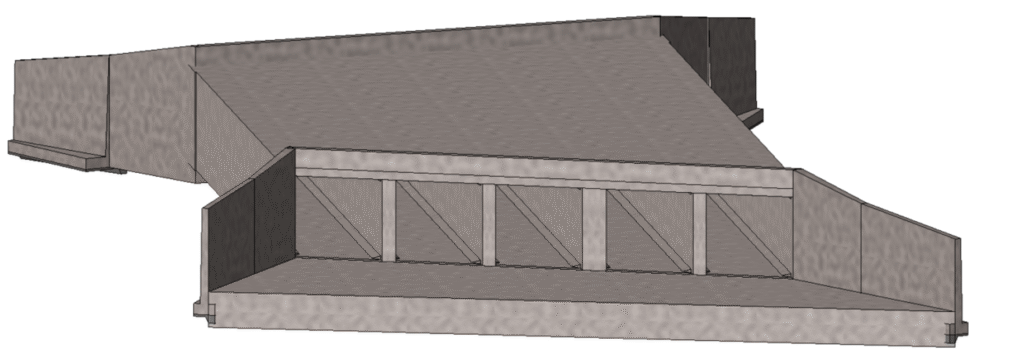

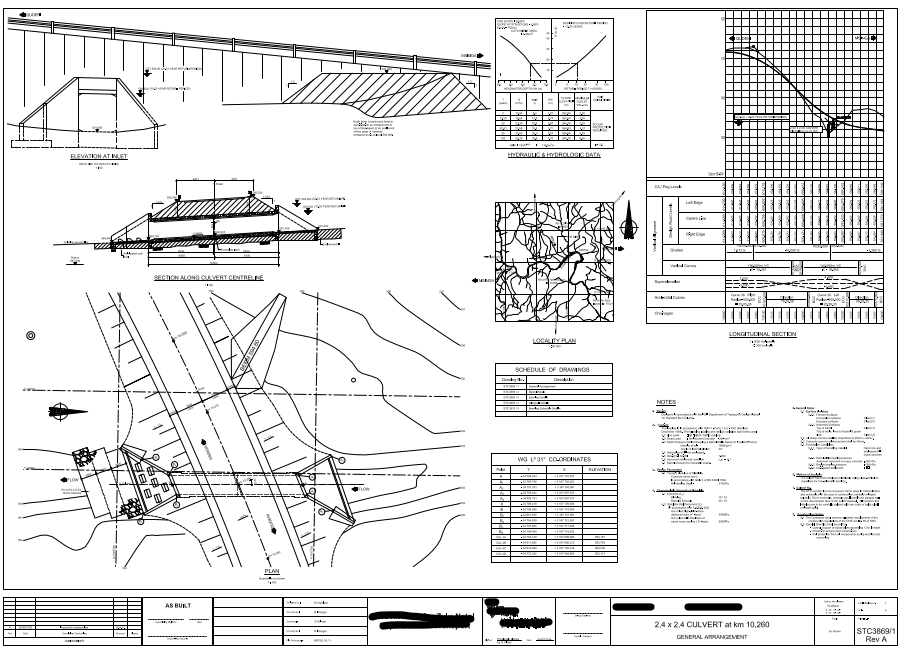

During my bridge design period, the CEO of the company I worked for provided a vision for pushing the company into what he called “digital transformation”. Placing the focus on generative design and automation. This was about the time when parametric modelling started to become prevalent (find out more about parametric modelling here). The company I worked for had developed, in the 1980s, a design manual which simplified the design of standard reinforced concrete box culverts. The user would simply peruse the manual and end up with a fully designed culvert (see below pictures of culverts). With that manual came standard drawings covering all geometric scenarios. Since the development of the standard drawings in the 1980s, the only enhancement of the manual was the development of AutoCad drawings to supplement the standard paper drawings.

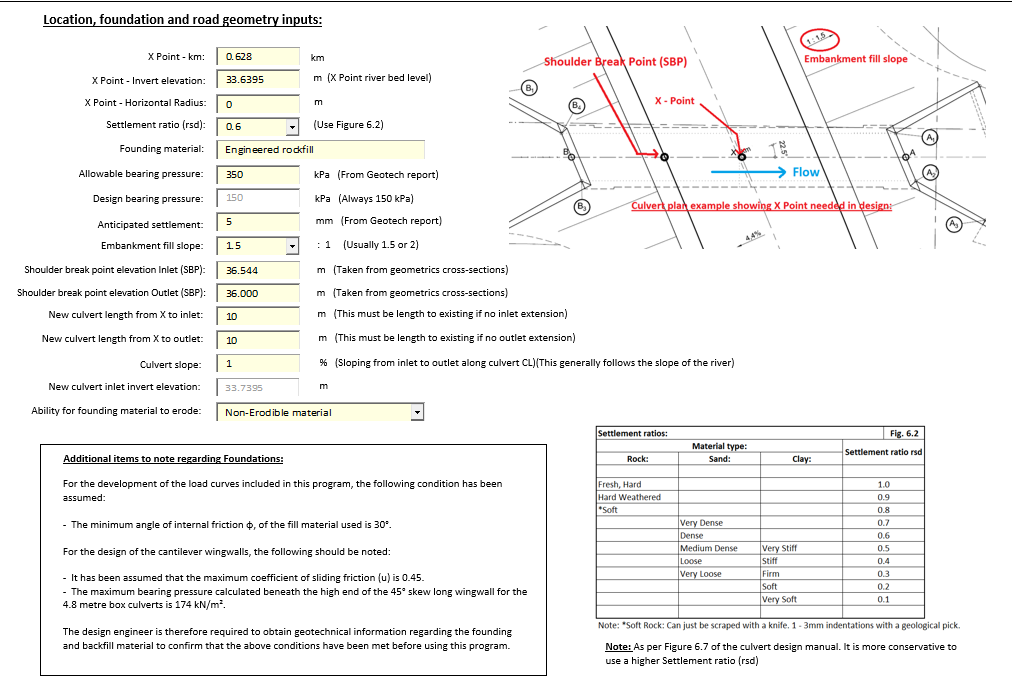

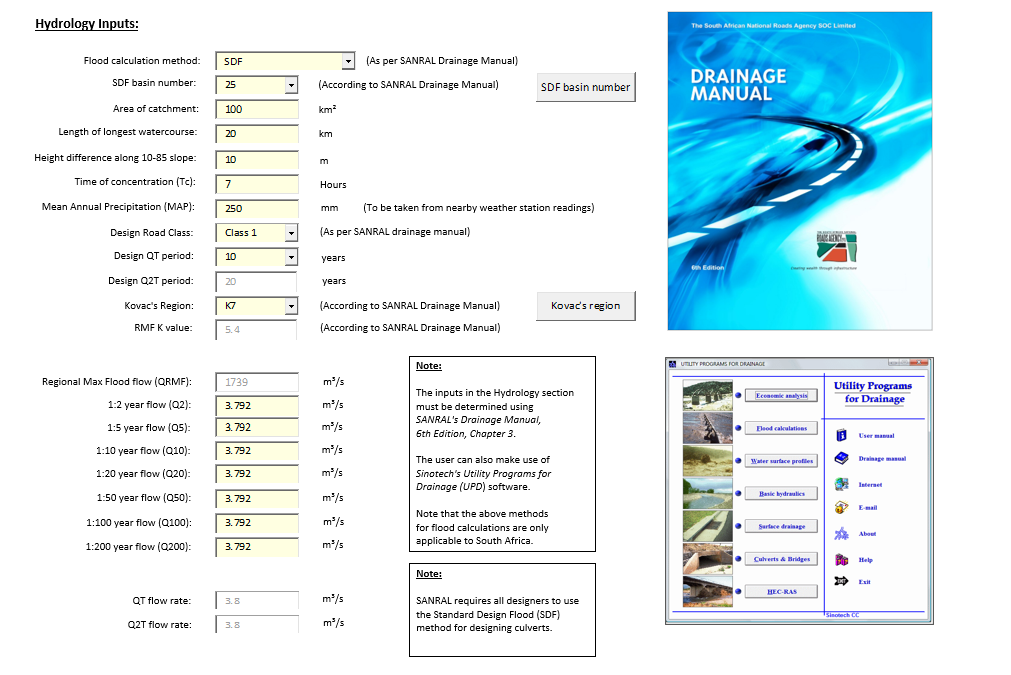

A colleague of mine had an idea to take the AutoCad standard drawings to the next level. The idea was to make a 3D parametric model of a culvert using an AutoDesk piece of software called Revit. This would be accompanied by 2D parametric drawings. The models and drawings were to be accompanied by an excel input sheet that would provide all the necessary inputs to automatically update the 3D and 2D details. By simply using the excel spreadsheet, the Engineer could have a full design and set of drawings within a couple of hours. This would then reduce design and drafting time from about 3 weeks, to 3 hours. The idea seemed enticing to management and we were thus given time and budget to develop this tool.

So why excel? Well, the only method familiar to us to automatically update parametric details in Revit was using excel together with a Revit plugin called Dynamo. It made sense to use Excel with most civil engineers using it for calculations and planning. If I’d known better at the time, I would have pushed to have a native desktop app be developed.

My task within this project was to create the excel program. It required a user interface which I decided to build with Excel VBA (see below screenshots of the program). To understand all of the required user input and automate the design, I needed to convert the entire design manual into code. All of it done in VBA. We decided to integrate an existing spreadsheet that automated bill of quantities (BOQs). We also programmed the automatic creation of bar bending schedules. This was needed as we did not have 3D parametric details for reinforcing. It was also decided to produce automated calculation sheets to help engineers check the outputs. After some months we achieved our goal of creating this tool and it did indeed significantly reduce labour costs. This was the first piece of useful software that I helped create. The irony of it all was that the company lost some key clients and the major box culvert work all but dried up, leaving us simply with only using the tool to cost tenders and reduce labour costs within these tenders. Therefore user feedback and iterating through versions didn’t happen. I left the company not knowing what happened to the tool and haven’t kept up with the industry so can’t tell if it left an impact anywhere. Overall the tool worked. Drawings were created in a couple of hours. We solved the problem and had an effective prototype. We simply lacked the support and know how to make use of it.

Here are some lessons learned:

- Adequate version control was not maintained;

- Half the team didn’t understand programming so the tool was a hybrid between excel spreadsheet formulas and VBA. We should have looked for more developers to join the team;

- No thought was put into making the tool accessible to the wider industry but rather only to benefit our team. i.e. sell it as a SAAS product or plugin to Revit;

- Auto populating cells in Excel using VBA was very slow;

- The company and the management had zero knowledge on software creation and monetization. Civil engineering consultancies are people businesses, not software businesses;

- Error handling was a nightmare with how complicated the tool was set up;

- Getting the tool into users hands as quickly as possible is vital for rapid iteration. With having only our team as the users of the tool there was no unbiased feedback loop;

- Too much emphasis on many features instead of one killer feature;

- The design codes and standards used were South Africa centric. Especially with hydraulic modelling;